Definition and Basic Concepts

Ceramics are non-metal materials. We make them from compounds like oxides, carbides, or nitrides. Common elements include silicon, aluminum, magnesium, calcium, and zirconium. Ceramics come in three forms: crystalline, amorphous, or composite. People use them for clay pottery and also for electronics and engineering.

Refractories are a special type of ceramic. They keep their strength at very high temperatures—starting at 1,000 °F (538 °C) and often higher. General ceramics can’t handle what refractories do. Refractories resist intense heat stress, heavy wear, and chemical damage. I recommend them for tough industrial jobs in furnaces, kilns, reactors, and blast furnaces. The iron and steel industry uses about 70% of all refractories.

Key Properties and Composition

Ceramics: You can fire pottery at ~900–1200 °C. Some advanced types work above 1600 °C.

- Examples: silicon dioxide (SiO₂), aluminium oxide (Al₂O₃), magnesium oxide (MgO), zirconium oxide (ZrO₂).

Refractories: They must work at ≥1,000 °F (538 °C). Some handle up to 2,000 °C. Materials include high-alumina (≥50% alumina), silica, magnesia, and non-oxides like carbides and nitrides.

Categories and Examples

Ceramic Categories:

- Structural ceramics: bricks, tiles

- Whitewares: porcelain, earthenware

- Engineering ceramics: spark plugs, medical implants, electronic parts

Refractory Types:

- Shaped forms: bricks, blocks

- Unshaped forms: castables, ramming mixes

- Ceramic fibers: insulation blankets for furnaces

Physical and Functional Differences

Ceramics can be porous or dense. They can be tough or brittle. No specific temperature defines them.

Refractories need these features:

- High melting points (higher than standard ceramics)

- Resistance to thermal shock

- Stability against chemicals in harsh environments

- Different heat conductivity—some conduct heat (like silicon carbide), others insulate (like calcium silicate).

Major Raw Materials and Service Temperatures

Common refractory materials include aluminium, magnesium, silicon oxides, zirconia, calcium, nitrites, carbides, silicates, borides, and graphite.

Temperature ratings for insulation:

- Up to 1,100 °C: Heat-resistant insulation

- Up to 1,400 °C: Refractory insulation

- Up to 1,700 °C: High refractory insulation

- Up to 2,000 °C: Ultra-high refractory insulation

Key Differences Between Ceramics and Refractories

I recommend comparing ceramics and refractories based on temperature resistance, intended use, and physical properties. These are the most important factors.

Purpose and Application

Ceramics: You’ll find them in tableware, floor tiles, electrical insulators, and cutting tools. They appear in everyday home products and general industrial items.

Refractories: Made for extreme heat and heavy industrial work. I see them most often lining kilns, furnaces, and reactors. They also insulate equipment in metal, glass, and cement plants.

Temperature Resistance

Ceramics: Standard ceramics work between 200°C and 1500°C. The exact range depends on the material.

Refractories: Built to stay strong above 1500°C. Here are some examples:

- Oxide-bonded silicon carbide reaches 1450°C.

- Nitride-bonded SiC goes up to 1550°C.

- High-purity alumina refractories exceed 1600°C.

- Zirconia refractories handle temperatures near 2200°C.

Mechanical Strength and Durability at High Temperatures

Typical Ceramics: They lose strength when heat increases.

Refractories: They keep their strength even at high temperatures. R-SiC and nitride-bonded SiC stay strong above 1500°C. High-alumina and mullite refractories perform well but are less tough.

Thermal Shock Resistance

Ceramics: Many crack when temperature changes quickly.

Refractories:

- Built to resist thermal shock.

- Recrystallized SiC (R-SiC) has low thermal expansion and high thermal conductivity.

- At 1000°C, it conducts 40–50 W/m·K.

- This beats alumina, which has lower conductivity and higher expansion.

Chemical Resistance

Ceramics: Their resistance to corrosive agents varies.

Refractories:

- Made to resist corrosive slags, molten metals, acids, and bases.

- Alumina handles basic slags and oxidizing conditions well.

- Zirconia works in direct contact with molten metals and glass.

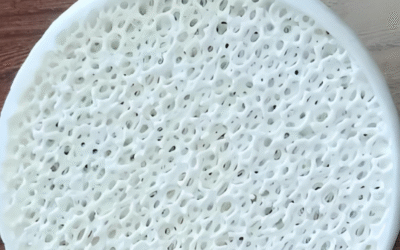

Porosity and Density

Ceramics:

- Can be porous like pottery.

- Can be dense like insulators.

Refractories:

- Porosity is controlled to match the job.

- Modern methods like Direct Ink Writing (DIW) customize porosity and surface features.

- This improves insulation or mechanical performance.

Real-World Examples and Data

Refractory Types and Stats:

- Firebrick (alumino-silicate): lines kilns and furnaces

- Silicon carbide (R-SiC): stays strong up to 1650°C, conducts 40–50 W/m·K

- Zirconia: works up to 2200°C, conducts below 3 W/m·K

- Mullite: general furnace lining

- Magnesite-chromite: lines steel industry equipment

Ceramic Examples:

- Porcelain and earthenware tableware

- Glazed and unglazed tiles

- Alumina and steatite electrical insulators

- Alumina and silicon nitride cutting tools

Comparison Table

| Property | Ceramics (Typical) | Refractories (Selected) |

|---|---|---|

| Service Temp (°C) | 200–1500 | 1400–2200+ |

| Application | Tableware, tools | Kilns, furnaces, reactors |

| Thermal Conductivity (W/m·K) | 1–6 (Alumina) | 40–50 (R-SiC), <3 (ZrO₂) |

| Thermal Expansion (10⁻⁶/K) | 6–9 | 4–5 (mullite), higher (ZrO₂) |

| High-Temp Mechanical Strength | Moderate | High (at elevated T) |

| Thermal Shock Resistance | Low–Moderate | High (R-SiC, Mullite) |

| Chemical Resistance | Varies | Engineered, high-resistance |

| Typical Form | Pots, insulators | Bricks, fibers, castables |

Summary

Ceramics and refractories differ in service temperature, high-temperature strength, shock resistance, chemical resistance, and core uses. All refractories belong to the ceramics group. But their properties, work environments, and industry roles make them a vital material for extreme industrial needs. Based on my experience, choosing the right type depends on your specific heat and chemical requirements.

Classification of Ceramics and Refractories

I recommend learning how we classify refractories and ceramics. This helps you see their differences and where they overlap.

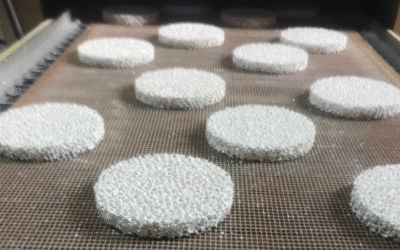

Physical Form Classification (Refractory Shapes)

Shaped Refractories: Products made with set forms, like bricks and blocks.

- Standard shapes: These follow industry norms (example: 230 × 114 × 65 mm brick). Machines press them for uniform sizes.

- Special shapes: Custom-molded to fit specific equipment. Think wedge-shaped bricks for rotary kilns or furnaces.

Unshaped (Monolithic) Refractories: These come without a set shape. They take form when you install them.

- Types include: plastic refractories, ramming mixes, castables, gunning mixes, and mortars.

- You can apply them as seamless linings in blast furnaces and ladles. They work great for patching repairs in steel works.

Insulating Forms: This includes ceramic fiber bricks and refractory ceramic fiber blankets. I often see them in furnace and kiln insulation. They reduce heat loss because of their low density and high thermal resistance.

Chemical Composition Classification (Acidic, Basic, Neutral)

Acidic Refractories:

- Base materials: silica and fire clay (SiO₂-rich).

- Applications: These resist acid slags and gases. They’re common in glass and ceramics manufacturing.

- Example: silica brick, fire clay brick.

Basic Refractories:

- Main components: magnesia, dolomite, or chrome-magnesia (≥85% MgO for magnesite brick).

- Use cases: Steelmaking furnaces need these to resist basic slags.

- Example: magnesite brick, dolomite refractory.

Neutral Refractories:

- Made from alumina, chromia, or carbon.

- These suit shifting or unpredictable furnace atmospheres. They resist attack by both acid and basic slags.

- Example: high-alumina brick, chromite refractory, carbon-based products.

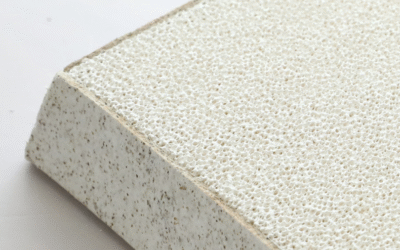

By Functionality and Density

Dense Refractories: High-density materials (>120 lb/ft³). These handle abrasion, slag, and chemicals in industrial furnaces.

- Example: fireclay bricks (about 75% of all refractories are fireclay based) and magnesia bricks.

Insulating Refractories: These focus on thermal insulation. Lower densities (4 to 70 lb/ft³). You can use them as backup linings to keep heat in and boost energy efficiency.

- Example: insulating firebrick and ceramic fiber insulation panels.

Key Refractory Types and Raw Materials

Common refractory products:

- Fireclay bricks (hydrated aluminum silicates, the most common type)

- Silica bricks (acidic)

- High-alumina bricks (neutral)

- Magnesite bricks (basic)

- Dolomite refractories (basic, calcium-magnesium carbonates)

- Chromite refractories (neutral)

- Refractory ceramic fibers (amorphous aluminosilicates)

Essential raw materials:

- Oxides: alumina (Al₂O₃), magnesia (MgO), silica (SiO₂), zirconia (ZrO₂), chromia (Cr₂O₃)

- Non-oxides: silicon carbide (SiC), silicon nitride (Si₃N₄), borides, graphite

Classification of Ceramics

Traditional ceramics: Pottery, porcelain, and bricks. These have lower thermal resistance. You see them in everyday use.

Advanced ceramics: Engineers create these for special roles in electronics, medicine, structural, or industrial uses. Sometimes they overlap with refractories if designed for high-temperature work.

Properties of Refractories vs. Ceramics

I believe understanding the key differences between refractories and ceramics is critical. You need to pick the right material for high-temperature or harsh conditions. Both use inorganic, non-metallic elements. But their performance differs a lot under extreme stress.

Thermal Properties

Refractories:

- Exceptional thermal resistance. They withstand temperatures above 1500°C.

- Melting points can exceed 2000°C. Alumina refractories melt at about 2050°C. Magnesia bricks melt at around 2800°C.

- I recommend refractories where continuous or extreme heat is present.

Ceramics:

- Good at handling heat. But upper-use temperatures are much lower.

- Porcelain is limited to about 1200°C.

- High-purity alumina ceramics can reach 1750–2000°C. But such grades cost more and are less common.

Mechanical Properties

Refractories:

- High compressive strength. Often exceeding 20 MPa for basic bricks at room temperature.

- Moderate tensile strength. But strong resistance to abrasion and mechanical impact. This is vital in furnace linings and blast furnaces.

- They maintain form and function even under thermal cycling.

Ceramics:

- Very hard. Alumina has a Mohs hardness of ~9. Silicon carbide reaches ~9.5. They are also wear-resistant.

- Poor fracture toughness means they are brittle. They can fail under impact or sharp stress.

Chemical Stability and Resistance

Refractories: Built for chemical inertness in tough industrial settings. They resist acids, bases, slags, and furnace gases. Major classes:

- Basic (magnesia, dolomite): high resistance to iron-rich slags.

- Acidic (silica, fireclay).

- Neutral (alumina, chromia, carbon): versatile under changing conditions.

Ceramics: Stable to most chemicals. But not always optimized for molten metals, slags, or industrial acids and bases. Suitability varies by composition. Standard ceramics lack the chemical engineering found in refractories.

Corrosion and Erosion Resistance

Refractories: Built for high corrosion and erosion resistance. I suggest them for molten slag, hot metals, and reactive gases. Magnesia bricks, for example, thrive in steelmaking. High slag resistance is critical there.

Ceramics: They show general resistance. But most traditional ceramics degrade or fail in aggressive environments.

Physical Properties – Density and Porosity

Refractories:

- Density ranges from 1.8–3.1 g/cm³ (fireclay to magnesia).

- Porosity can be high in insulating grades (20–30%) for thermal retention. Or low in dense structural refractories.

- Low thermal conductivity in insulating types (1–2 W/m·K). But can be higher in some dense grades.

Ceramics:

- Density: 2.3–3.9 g/cm³ (from kaolin to high-alumina ceramics).

- Variable porosity. Can be non-porous (<1%) in engineered electrical ceramics. Or porous (25%) in traditional pottery.

- Strong in electrical and thermal insulation. Quartz: 1.4 W/m·K. Alumina: up to 30 W/m·K in high-purity forms.

Comparative Property Table

| Property | Refractories | Ceramics |

|---|---|---|

| Max. Temp (°C) | >1500, up to 2800 (MgO, Al₂O₃, SiC) | ~1200–2000 (porcelain, alumina, SiC) |

| Melting Point (°C) | Up to 2800 (MgO) | 1750–2000 (high-purity alumina) |

| Hardness (Mohs) | 6–9 | 6–9.5 |

| Density (g/cm³) | 1.8–3.1 | 2.3–3.9 |

| Porosity (%) | 5–30 | <1–25 |

| Thermal Conductivity (W/m·K) | 1–2 (fireclay); 10+ (dense alumina) | 1.4 (quartz); up to 30 (alumina) |

| Chemical Resistance | Slags, acids, bases | General (less for molten metals/slags) |

| Applications | Furnace linings, blast furnaces, kilns | Tableware, structure, insulation, tech |

Industrial Examples

Refractories:

- Magnesite brick: ≥85% MgO. Melting point ~2800°C. High density. Shock and corrosion resistant. Crucial for blast furnaces.

- Alumina brick: ≥50% Al₂O₃. ~2050°C melting. High load stability.

- Dolomite brick: Used in converter linings. Melting point ~2300°C.

- Carbon-graphite: I like this refractory for electric arc furnaces. It handles rapid thermal cycling.

Ceramics:

- Porcelain: Fired at 1000–1400°C. Mohs hardness ~7. Not suited for intense industrial heat or slag.

- Alumina ceramics: ≥90% Al₂O₃. Melting point ~2050°C. Excellent hardness. Electrical insulation.

- Silicon carbide: Melting point ~2700°C. Mohs hardness ~9.5. Outstanding wear resistance. Used in some refractory applications.

Key Takeaways

About 70% of global refractory production goes to iron and steel manufacturing.

The main property differences:

- Refractories excel in refractoriness, load strength, chemical and abrasion resistance, porosity, and service under thermal shock.

- Ceramics offer hardness, wear resistance, and insulation. But they fracture or degrade under stresses where refractories excel.

Pricing and availability depend on raw material purity, shape, and property engineering. High-purity alumina and magnesia refractories cost more. Their performance in extreme conditions justifies the price.

Based on my experience, all refractories are ceramics or ceramic-like. But refractories are engineered to survive aggressive temperatures, mechanical forces, and chemical attack. This is a crucial advantage for heavy industry.

Applications: Refractory vs. Ceramic Materials

I recommend understanding the difference in applications when you decide between refractories and ceramics. Each type serves unique roles. These roles depend on properties, performance data, and work environments.

Refractory Applications: High-Temperature and Industrial Use

Industries need materials with extreme heat and chemical stability. Refractories fill this need:

-

Metallurgy:

Steel, aluminum, copper, and glass furnaces need linings. Ladles and kilns also require them. These materials handle rapid temperature changes and harsh environments. -

Kiln Furniture:

R-SiC and other engineered ceramics work as shelves, decks, and supports. They go in kilns or oven cars. They provide mechanical strength. They also give thermal stability during firing. -

Energy and Power Generation:

Boilers, incinerators, and power plant furnaces use refractories. These materials resist flames and harsh combustion gases. They help transfer energy efficiently. -

Chemical and Petrochemical Industries:

Reactors, reformers, and pipelines need special linings. These linings endure corrosive chemicals and sustained high temperatures. -

Automotive and Aerospace:

Exhaust insulation and heat shields use refractories. They protect sensitive parts from extreme heat. -

Domestic Appliances:

High-temperature ovens and fireplaces contain refractories. They offer heat resistance and safety.

Refractory Product Data and Performance

| Material | Max Temp (°C) | Mohs Hardness | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corundum (α-Al2O3) | 1900 | 9 | Abrasives, wear parts, premium refractories |

| Alumina (Al2O3) | 1700 | 8.5–9 | Furnace linings, tubes, electrical insulation |

| Cordierite | 1300 | 6–7 | Kiln shelves, supports, thermal shock components |

| Mullite | 1600 | 6–7 | Kiln linings, crucibles, burner tiles |

| Corundum Mullite | 1700 | 8–8.5 | Structural refractories in demanding contexts |

Refractory Ceramic Fiber (RCF):

- Forms: Bulk fiber, blankets, boards, modules, papers, custom shapes.

- Service temperature: 1200–1600°C. This allows efficient, lightweight linings for kilns and furnaces.

- Energy savings: RCF cuts fuel consumption. It improves heating and cooling cycles. Dense refractory linings can’t match this performance.

Thermal Conductivity:

- High-purity alumina: ~5–6 W/m·K at 1000°C

- Recrystallized SiC: ~40–50 W/m·K at 1000°C

- Your choice depends on your needs. Do you need rapid heat transfer? Or do you need excellent insulation?

Ceramics (Non-Refractory): Broad and Versatile Uses

Ceramics outside the refractory category serve many sectors. These sectors don’t involve extreme heat:

- Structural: Bricks, tiles, building materials, dinnerware, and art pottery.

- Electrical: Insulators, circuit substrates, piezoelectric devices. These are vital for electronic and electrical systems.

- Chemical: Filter membranes, catalyst supports, chemical seals.

- Aesthetic: Decorative tiles, porcelain, sanitary ware, and artistic ceramics. I see these used often in residential and architectural projects.

Keys for Application Selection

I recommend refractories for applications with sustained heat above 1000°C. Use them for aggressive chemical attack. Use them for stability during thermal cycling.

I suggest general ceramics for insulation, structural support, and aesthetic appeal. Use them for electrical insulation at moderate to low temperatures.

Evaluate these factors:

- Operating temperature requirements

- Expected exposure to thermal shock, chemicals, or abrasion

- Service environment and desired product life cycle

In summary:

– Refractories work best in industrial furnace linings. They excel in high-temp insulation. They perform well in wear-resistant and corrosive environments. Glass and metal processing rely on them. They save energy as linings.

– General ceramics shine in homeware, tiles, and electronics. They work well in chemical processing and decorative arts.

Based on my experience, your selection must match your process demands. Consider temperature, environment, and longevity.

Summary: Key Differences Between Refractories and Ceramics

Refractories are engineered ceramic materials designed for high-temperature stability (often exceeding 1600–1900°C). They resist severe thermal shock, chemical attack, and mechanical stress.

Ceramics include a larger group of inorganic, non-metallic materials. This group covers both refractories and everyday products like tableware, tiles, and electrical components. Not all ceramics can handle the tough requirements of refractory use.

Key Compositional and Performance Differences

Refractory Compositions:

- Main oxides: Al₂O₃ (Aluminum oxide), SiO₂ (Silicon dioxide), MgO (Magnesium oxide), ZrO₂ (Zirconium oxide)

- Also uses carbides, nitrides, borides, graphite, and silicates for better performance under harsh conditions

Standard Ceramics:

- Uses clays, feldspars, silica, and talc

- Found in pottery, porcelain, tiles, and electronics

Characteristic Properties (Select Data Table)

| Property | Refractories (e.g., Al₂O₃, Mullite, R-SiC) | Standard Ceramics (Porcelain, Earthenware) |

|---|---|---|

| Max Service Temp (°C) | 1300–1900 | 600–1200 |

| Mohs Hardness | 6–9 | 5–7 |

| Thermal Shock Resistance | Good–Excellent (Cordierite, Mullite, R-SiC) | Low–Moderate |

| Chemical Resistance | Excellent (Al₂O₃, ZrO₂, R-SiC) | Moderate to Low (varies) |

| Thermal Conductivity | High (R-SiC: 40–50 W/m·K @ 1000°C) | Low–Moderate |

| Industry Usage | Metallurgy, kilns, furnaces, chemical plants | Tableware, tiles, sanitary ware, electronics |

Application Examples & Cost Considerations

High-cost refractories (Corundum/Al₂O₃, ZrO₂): I recommend these for critical, high-stress environments. Think glass melting and metal processing. Save them for the most aggressive conditions.

Medium-cost refractories (Mullite, Cordierite): These are common in kiln furniture, supports, and industrial furnace linings. Based on my experience, they offer good value for typical industrial applications.

Raw material ratios in refractories:

- Al₂O₃: 30–95%

- SiO₂: 10–70%

- MgO: up to 97% (magnesia bricks)

- ZrO₂: 85%+ (zirconia bricks)

Unique Properties and Functionality

Refractories:

- They keep their structural strength at peak industrial temperatures. Standard ceramics cannot do this.

- They show low thermal expansion. This helps them resist thermal shock.

- They resist corrosion by slag, molten metals, acids, and aggressive gases. For example, Al₂O₃ fights slag, and R-SiC resists oxidation.

- They use mineral aggregates and advanced bonding (oxides, nitrides, carbons) to last longer.

Standard Ceramics:

- They focus on durability, looks, or electrical performance at low to mid temperatures.

- They don’t have the special design needed for ultra-high temperatures, chemical extremes, or mechanical stress.

Engineering Selection and Industry Impact

Engineers choose materials based on operating temperature, thermal cycling, chemical exposure, mechanical load, and cost. I suggest weighing all these factors carefully. About 70% of refractories go to the iron and steel industry for extreme furnace applications. This shows their high-value, specialized role.

My take:

– Refractories are the high-performance heart of industrial ceramics. They combine melting point, structural strength, thermal shock resistance, and chemical durability. The cost is higher, but standard ceramics can’t match their performance.

– General ceramics are still essential for many applications. But they don’t meet the strict technical needs of refractory uses. I like to think of refractories as the elite athletes of the ceramic world—built for the toughest challenges.