Some ceramic materials soak up water like a sponge. Others push it away. This basic difference shows us two separate types in ceramic engineering: porous and dense ceramics. Both start from similar raw materials. But their internal structures give them very different properties. Each type works best for specific jobs—porous ceramics for medical implants, dense ones for furnace linings.

Why does this matter? If you’re picking materials for filtration systems, thermal insulation, or biomedical devices, you need to know the difference. The answer lies in their tiny internal structure. How they’re made matters too. Those small air pockets—or the lack of them—change how these materials perform. You might be an engineer checking material options. Or maybe you just want to understand how these materials work. Either way, pore structure affects performance more than most people realize.

What Are Porous Ceramics? Core Definition and Structure

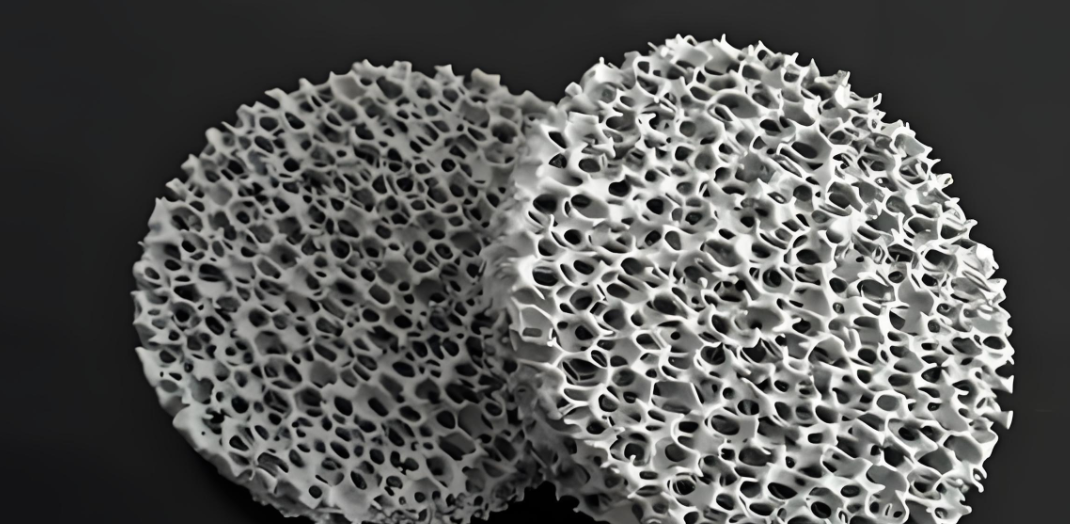

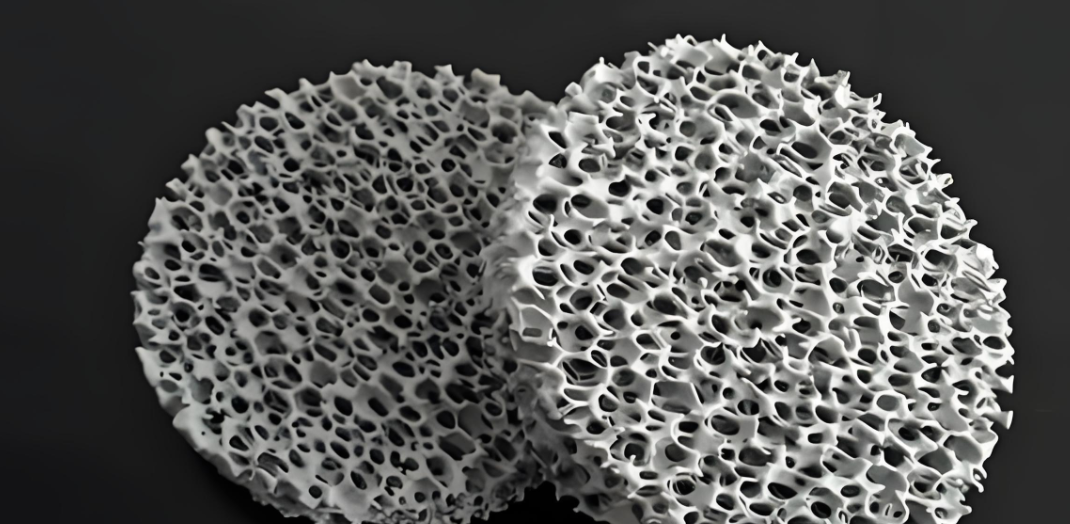

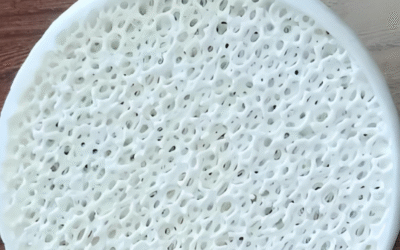

Porous ceramics are engineered inorganic solids. Think materials like zirconia and alumina. Manufacturers create them with controlled networks of voids (pores) spread throughout their structure. These pores aren’t accidents. Production teams create them on purpose. The manufacturing process fires ceramic powders below their melting point. This hardens the material but keeps the designed void spaces intact. The result? You get a material that keeps ceramic’s core strengths—heat resistance, chemical stability, and mechanical durability. But it weighs much less because air fills those internal spaces.

The pore structure determines everything about performance. Three main configurations exist:

-

Open-cell pores: Interconnected channels run through the material. They create pathways for fluids and gases to flow from one surface to another. This structure enables filtration and capillary action.

-

Closed-cell pores: Isolated bubbles get trapped within the ceramic matrix. No permeability. Excellent thermal insulation. Lower overall density.

-

Mixed structures: Random combinations of open and closed pores. Or pore arrangements that align in lines for specific directional properties.

Pore dimensions matter just as much as their connectivity. Engineers classify them into three categories based on diameter: macroporous (over 50 μm), mesoporous (2–50 μm), and microporous (under 2 μm). Real-world production can create pores ranging from a few dozen micrometers up to 470 μm. This uses extrusion techniques.

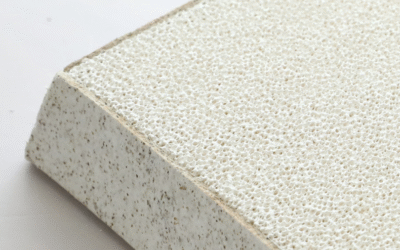

Porosity percentage has a direct impact on density and strength. Most porous ceramics operate in the 20–40% porosity range. Specialized microporous versions reach 10–90%. Some wood-templated designs push porosity up to 70%. This internal space reduces density to 0.5–3 g/cm³. That’s far below dense ceramics with under 5% porosity. Well-designed porous ceramics can still support loads 10,000 times their own weight. This happens when pores align in one direction.

What Are Regular (Dense) Ceramics? Definition and Characteristics

Dense ceramics pack their atoms tightly together. No air gaps. No voids on purpose. These solid materials reach densities above 95% of what’s possible. You get a solid, compact structure. Strength and toughness define these materials. Porous ceramics are lighter. Dense ceramics give you better performance in extreme conditions.

Density numbers show the differences. Different ceramic types have different weights per volume:

-

Zirconia (ZrO₂) tops the chart at 5.6–6.1 g/cm³—the heaviest technical ceramic

-

Alumina (Al₂O₃) sits at 3.6–3.9 g/cm³, mixing density with flexibility

-

Silicon Carbide (SiC) and Silicon Nitride (Si₃N₄) cluster around 3.1–3.3 g/cm³

-

Boron Nitride (BN) drops to 1.85–2.9 g/cm³, the lightest engineering ceramic

-

Traditional porcelain reaches 2.3–2.5 g/cm³ with nearly 0% porosity

Most engineering ceramics fall between 2.5–6.3 g/cm³. Anything above 2.5 g/cm³ means dense structure. Below that, you’re looking at porous materials.

How Density Affects Performance

Higher density means fewer paths for cracks to spread. Zirconia at 6.0 g/cm³ beats silicon carbide at 3.1 g/cm³ for crack resistance. This tight structure brings clear benefits:

Mechanical properties: Compressive strength is about 10 times higher than tensile strength. This 10:1 ratio holds across dense ceramics. Strong atomic bonds make these materials harder than most metals. They have high stiffness, too. But there’s a trade-off. These materials are brittle. They don’t handle impacts well. Thermal shock can damage them.

Environmental toughness: These materials stay stable in harsh chemicals. They resist wear from abrasion. Corrosion can’t get through the dense structure. Working temperatures go above 1000°C. They expand very little from heat. Shape changes stay minimal under long-term loads.

Other traits: Most dense ceramics block electricity well. Heat moves through them at low to medium rates. They’re not transparent. You can machine them with the right tools. They’re harder to cut than metals, but still manageable.

Manufacturing Process: How They’re Made

Raw powder to finished ceramic takes two distinct paths. One builds solid, impenetrable structures. The other creates controlled void networks through the material. The difference goes beyond final density. It’s about distinct production techniques, firing temperatures, and how materials behave during making.

Dense Ceramic Production: Maximum Consolidation

Dense ceramics use a simple consolidation process. Manufacturers pack ceramic powders—alumina, zirconia, silicon carbide—into molds under extreme pressure.

Uniaxial pressing applies force from one direction. This compacts particles tight. Isostatic pressing squeezes from all sides at once. Air pockets vanish. These methods push particle-to-particle contact to maximum levels before firing starts.

Sintering temperatures reach 1400–1800°C. This often exceeds the materials’ melting points. At these extremes, atoms spread across particle boundaries. Grains grow. Gaps disappear. The ceramic reaches over 95% of theoretical maximum density.

Xiaomi’s factory shows this precision—10 million units per year with zero human workers on production lines. Digital twins simulate the sintering cycle first. They predict shrinkage rates and optimize energy use before physical production starts.

Porous Ceramic Techniques: Engineering Void Space

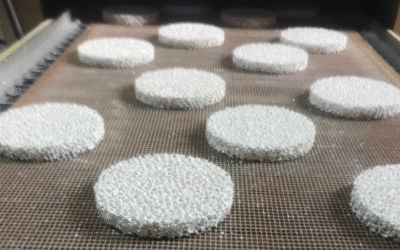

Porous ceramics need the opposite approach. You prevent full densification while keeping structural integrity. Four primary methods control pore formation:

Replica template method coats polymer or natural foams with ceramic slurry. After drying, high-temperature burnout vaporizes the organic scaffold. This leaves an exact ceramic replica with interconnected pores matching the original foam structure. Wood templates achieve up to 70% porosity this way.

Sacrificial pore formers mix temporary materials—starch, graphite, polymethyl methacrylate—into ceramic powder. Particle size sets final pore diameter. During firing at 600–1000°C, these additives break down and escape as gas. Voids form where they once sat. Production teams control pore size from 2 μm to 470 μm by picking different particle grades.

Direct foaming creates gas bubbles in liquid ceramic suspensions. Surfactants or mechanical agitation do this. Gelation freezes the bubble structure in place. Drying and firing convert the foam into rigid porous ceramic with 20–90% porosity. Initial foam density determines this range.

Partial sintering fires below full densification temperatures—1000–1300°C instead of 1600°C+. Particles bond at contact points but don’t merge. The gaps between particles become the pore network. This simpler method works for applications that tolerate less controlled pore structures.

Key Performance Differences: Side-by-Side Comparison

Density creates a performance gap. Porous ceramics and dense ceramics use the same base materials—alumina, zirconia, silicon carbide. But their internal structure pushes them in opposite directions. One trades mechanical power for versatility. The other maximizes strength but adds weight and blocks flow.

Mechanical Strength and Load Capacity

Dense ceramics win at compressive strength. Zirconia reaches 2,000 MPa under compression. Alumina hits 3,000 MPa. Their packed atomic structure has no weak points for cracks to spread. The 10:1 ratio between compressive and tensile strength stays consistent across all dense ceramic types—they resist crushing far better than pulling forces.

Porous ceramics work in a different range. At 40% porosity, compressive strength drops to 50–200 MPa based on pore design. That’s a 90% reduction compared to dense types. But aligned pore structures change this. Well-designed porous ceramics support loads 10,000 times their own weight along reinforced axes. This makes them useful for lightweight structures where traditional dense ceramics would add too much mass.

Thermal Performance and Insulation

Heat moves through dense ceramics at 20–30 W/m·K for alumina and silicon carbide. Their solid structure conducts thermal energy fast. This makes them ideal for heat sinks and kiln linings where you need quick heat transfer.

Porous ceramics trap air in their void networks. Air conducts heat at just 0.026 W/m·K. Even with ceramic surrounding those pockets, thermal conductivity drops to 0.1–2 W/m·K at 70% porosity. That’s a 95% reduction in heat transfer compared to dense versions. Furnace insulation and thermal barrier coatings use this dramatic difference.

Permeability and Filtration Capacity

Dense ceramics block all fluid flow. Zero porosity means zero permeability. They seal against gases and liquids.

Open-cell porous ceramics do the opposite. Connected channels create permeability rates from 10⁻¹⁵ to 10⁻¹¹ m² based on pore diameter. Macroporous structures (>50 μm pores) filter particles from water and industrial gases. Microporous versions (<2 μm pores) separate molecules in chemical processing. Dense ceramics can’t do this at all.

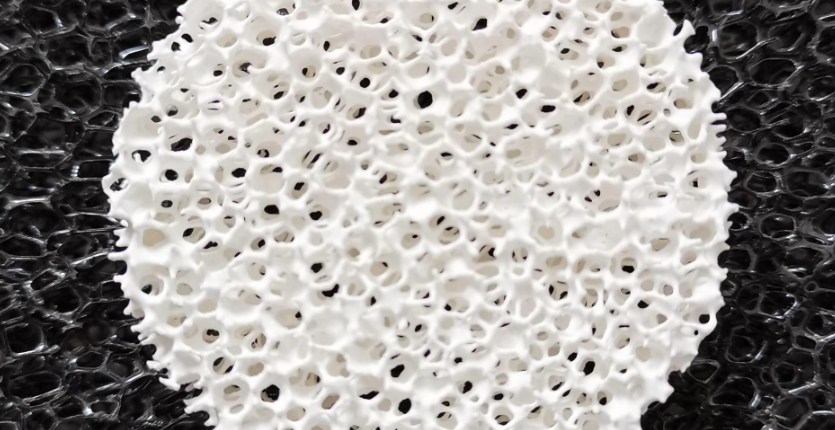

Pore Types and Their Functions in Porous Ceramics

Pores don’t all work the same way. Shape, size, and how voids connect inside porous ceramics decide what the material does. Engineers sort pores two ways: connection patterns and physical size. These categories predict real-world performance.

Classification by Connectivity

Open-cell pores link throughout the ceramic body. Fluid enters one side, moves through internal channels, and exits the other side. This drives pressure flow and capillary action. Mass transfer runs fast. Filtration systems and catalytic converters use this structure. Need particles or gases to move through? Open-cell design does that.

Closed-cell pores sit alone inside the ceramic. No paths connect them. Fluids can’t pass through. Trapped air gives great heat insulation. Weight drops but the shape stays stable. Furnace linings use closed-cell structures to block heat while staying strong.

Half open-cell setups mix both types. Some pores connect. Others stay sealed. This makes materials light but with varied fluid flow. Controlled gas release and selective filtration need this setup.

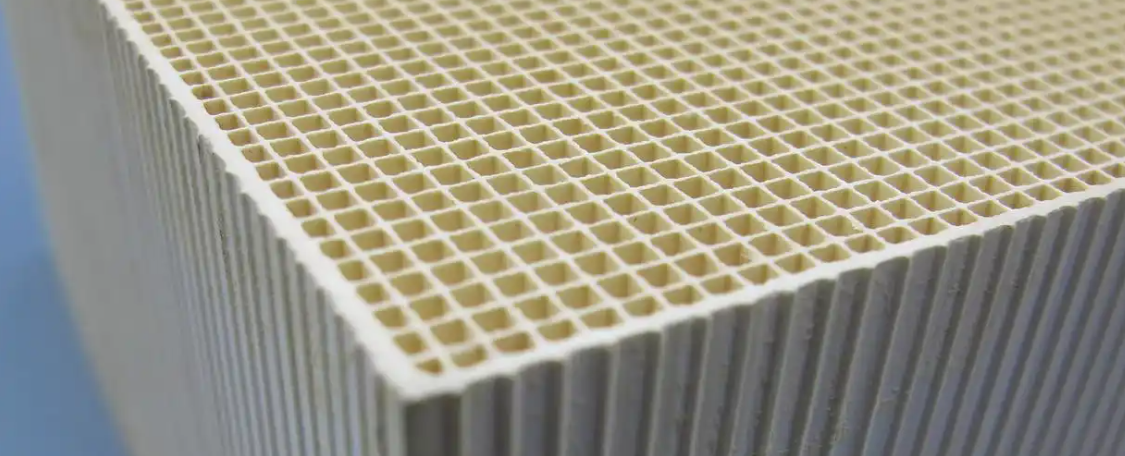

Pore direction matters too. 3D open pores connect in all directions. This boosts surface access. Catalyst supports and tissue scaffolds benefit from access in every direction. 2D slit-shaped pores stretch across two dimensions—good for directed fluid flow. 1D unidirectional pores run parallel through the material. Porous alumina with aligned round channels lifts fluids over 1 meter high. These aligned patterns stay 10 times stronger than random pore networks and keep flow high.

Classification by Pore Size

Diameter decides function. Three standard groups exist:

Microporous structures have pores under 2 μm (some standards use 2 nm). Think zeolites and gel materials. These tiny spaces create huge surface areas. Gas cleaning and molecular sieves need this small-scale setup.

Mesoporous ceramics range 2–50 μm across. This size boosts gas-solid contact. Catalyst supports work here. Surface area and flow resistance balance perfectly for chemical reactions.

Macroporous materials go over 50 μm. Large channels let particle-filled fluids pass without blocking. Molten metal filtering needs 50–500 μm pores to catch oxide chunks. Bone scaffolds use 100–500 μm for tissue growth and blood vessel formation.

Critical Performance Metrics

Engineers track four factors to check pore function:

Pore size spread shows the average diameter and range. Foam ceramic with 300 μm average pore size and tight spread filters the same way every time. Wide spreads make flow paths unpredictable.

Specific surface area measures internal surface in m²/g. Catalyst jobs need values over 50 m²/g. More surface creates more active spots for reactions.

Tortuosity shows how twisted the flow paths are. Straight channels score near 1.0. Complex networks hit 2–5. Higher twist slows movement but extends contact time—key for gas treatment.

Permeability shows how fast fluids flow under pressure. Measured in Darcy or m². A porous SiC filter shows 1.2×10⁻¹² m² flow with 12 MPa crush strength. This balance lets fluids pass while holding mechanical weight.

Manufacturing methods make different pore shapes. Replica foam templates produce bubble-like pores at 60–90% porosity. Strength stays low to medium. Extruded honeycombs form straight channels at 20–60% porosity with better strength. Pore-forming agents like starch or carbon black burn away during firing. This gives controlled pore sizes matching the starting particle size—anywhere from 1 μm to 470 μm based on additive choice.

Your pore type choice decides what the ceramic does. Need filtering? Pick open-cell macropores. Want insulation? Go with closed-cell micropores. Need catalysis? Choose mesoporous 3D networks. Each job needs specific pore design. Match connectivity, size, and spread to your needs.

Real-World Uses: Where Each Type Works Best

Industries pick ceramics based on physics—not style. Dense ceramics handle extreme conditions. Think crushing forces, rough wear, or harsh chemicals. Porous ceramics work best for fluid flow, heat barriers, or bone growth. Both types do important jobs, but they rarely compete for the same role.

Dense Ceramics: Built for Tough Jobs

Cutting tools and wear parts need dense silicon carbide and alumina. Machine shops use these ceramics to cut hardened steel. Metal tools can’t keep up with the speed. A silicon carbide insert stays sharp through 10,000+ cuts without resharpening. The density at 3.2 g/cm³ stops tiny cracks from forming during high-speed cutting.

Ballistic armor systems stack dense boron carbide tiles (2.5 g/cm³) or alumina plates (3.9 g/cm³) in body armor and vehicle protection. The solid structure breaks apart incoming bullets on impact. No gaps exist to create weak spots. Military ceramic armor stops rifle rounds that punch through steel plates of the same weight. You get protection at 40% less mass than metal options.

Industrial kiln linings use dense alumina and zirconia bricks to hold 1600°C molten glass and metal. These ceramics fight off chemical attacks from slag. They keep their strength through thousands of heating cycles. A single zirconia furnace lining runs for 5-7 years before you need to replace it.

Electronic insulators in power systems use dense alumina and porcelain to block electrical current. They pull heat away from parts at the same time. High-voltage transmission lines use alumina insulators rated for 500,000+ volts. Zero gaps mean no arcing through the ceramic body. Porous versions fail in this way.

Porous Ceramics: Made for Flow and Integration

Diesel particulate filters catch soot from exhaust gases. They use silicon carbide honeycomb structures with 65% porosity. Connected channels push exhaust through porous walls. These walls catch particles bigger than 10 μm. Over 15 million vehicles worldwide now use these filters to meet clean air rules. The system burns trapped soot at 600°C to clean itself. The ceramic stays intact.

Water cleaning membranes from porous alumina remove bacteria and floating solids. The pore networks measure 0.1–1 μm. City treatment plants push 50,000+ liters daily through ceramic filter banks. Polymer membranes break down over time. Ceramic versions run for 10+ years. Backwashing restores flow rates.

Bone replacement scaffolds from porous hydroxyapatite help new tissue grow after injury or disease. Surgeons place these ceramics with 70% porosity and 200 μm connected channels. The structure matches natural bone. Blood vessels grow into the scaffold within 4-6 weeks. New bone cells move in and slowly replace the ceramic through natural healing. Complete blending happens in 6-12 months.

Molten metal filtration uses porous silicon carbide or alumina foam to remove oxide bits from aluminum and steel casting. Foundries place ceramic foam filters (20-30 ppi pore density) in pour channels. Molten metal at 700-1500°C flows through. Solid dirt particles larger than 50 μm get trapped. This cuts defects in finished castings by 60-80% compared to unfiltered metal.

Heat shield panels for aerospace re-entry vehicles use porous silica tiles with 90% porosity and closed-cell design. Space Shuttle tiles handled 1650°C surface heat during re-entry. The aluminum underneath stayed below 175°C. Heat movement of 0.14 W/m·K made this huge temperature gap possible. Trapped air pockets did the work across just 50-100 mm thickness.

Choosing Between Porous and Regular Ceramics

Start with one question: Does your project need to block fluids or let them pass through? This tells you whether to pick porous or dense ceramics.

Water absorption rates show the difference clearly. Impervious ceramics absorb under 0.5%. Porous types take in over 7.0%. Semi-vitreous and vitreous grades fall in between at 0.5% to 7.0%. ANSI tile standards define these benchmarks for easy selection.

Why Pick Porous Ceramics

You need permeability, filtration, or fluid transport? Go with porous ceramics. Open pores larger than 50 nm create connected pathways.

Unidirectional pore designs lift water up to 1 meter height through capillary action. Urban heat control systems use this for passive water distribution. Hardwood-based ceramics have large vessel pores built in. Softwood templates create smaller pore structures. Both keep their natural pore networks after processing.

Weight reduction matters in aerospace and portable gear. Air-filled pores cut density. You still get ceramic’s chemical resistance. At 25.9% porosity, freeze-cast alumina delivers 512 MPa compressive strength. Hydroxyapatite bone scaffolds work at 70% porosity. They support 10 MPa loads and help tissue grow through 120–130 μm channels.

Surface area drives catalysis and insulation performance. Pore networks expand internal surface area massively. This increases how much the material can absorb. It also creates thermal barriers. Air in pores blocks electrical current better than solid materials do.

Why Pick Dense Ceramics

Outdoor installation? Water immersion? Freeze-thaw cycles? You need impervious non-porous ceramics.

Here’s proof: Semi-vitreous tiles with 4% water absorption broke apart during winter. Porcelain at 0.05% absorption fixed the problem. Water gets trapped in pores and expands during freezing. Even small absorption rates cause cracks.

Load-bearing uses need zero open porosity. Sinks, countertops, and floors face constant stress. Fire ceramics above 1,260°C (2,300°F) to close pore networks. Glass forms inside and creates the density you need for strength.

Non-porous types need less maintenance. Glazed porcelain never needs sealing. Porous earthenware and stone need resealing regularly to stop stains and moisture damage. Commercial kitchens and busy public spaces can’t handle this extra work.

Conclusion

Porous ceramics vs. regular ceramics – it boils down to three key factors: structure, function, and where you’ll use them. Regular ceramics give you unmatched strength and impermeability for structural needs. Porous ceramics work best where you need controlled airflow, filtration, and lightweight properties. Think water purification systems and biomedical implants.

The right choice isn’t about which material is “better.” You need to match the ceramic type to your specific needs. Need mechanical strength and moisture resistance? Regular ceramics are your answer. Need filtration, insulation, or breathability? Porous ceramics deliver exactly that.

Manufacturing technologies keep advancing. The performance gap gets smaller. Customization options grow. You’re an engineer picking materials for your next project? Or maybe a buyer checking out suppliers? Here’s what matters: porosity percentage, pore size distribution, and manufacturing method. These three factors impact real-world performance.

Ready to source the right ceramic solution? Check your application’s main function first. Then let the material’s natural properties guide your decision.