Introduction to Low Melting Point Metals

Some metals turn from solid to liquid at low temperatures. This makes them useful in many industries, science labs, and tech products. Mercury stays liquid at room temperature, but other metals and alloys also melt at very low points.

Key Low Melting Point Metals (Excluding Mercury)

-

Cesium: This metal melts at just 28°C (82°F). You can liquefy it with the warmth of your hand. Cesium reacts fast with other substances. Scientists use it in atomic clocks for exact timekeeping. Oil and gas companies also use it in drilling fluids.

-

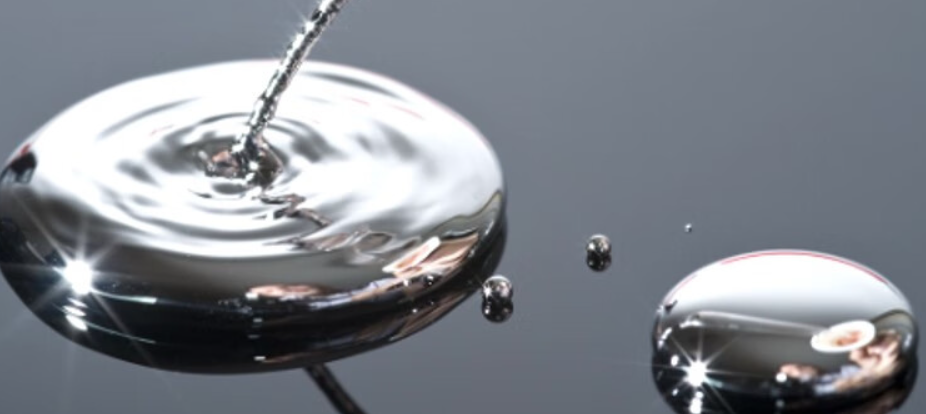

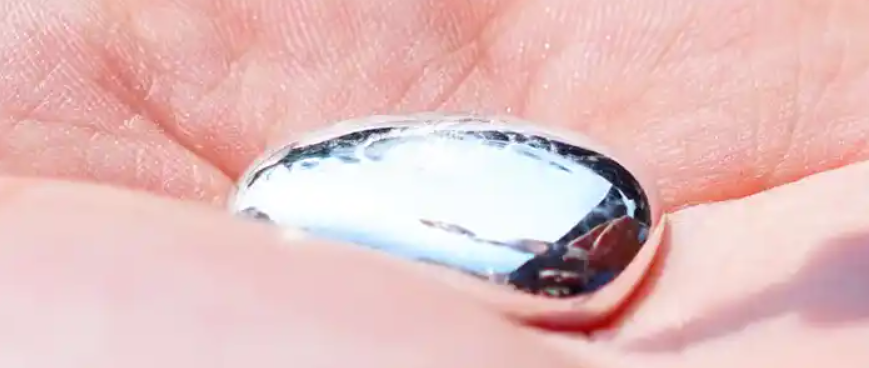

Gallium: Gallium melts at 30°C (86°F). It can dissolve in your palm. I recommend gallium as a safer choice than mercury because it is non-toxic. It works well in thermometers. Electronics makers use it for semiconductors. It’s also part of low-melting alloys like Galinstan.

-

Francium: This metal melts at 27°C (81°F). But it’s very rare and radioactive. Companies don’t use it. You’ll find it in scientific research labs.

-

Rubidium: Rubidium melts at 40°C (104°F). It reacts fast with other materials. Research teams use it in their labs.

Other Notable Metals

-

Potassium (63°C/145°F) and Sodium (98°C/208°F): These alkali metals are vital. Farmers use them in fertilizers. Chemical industries need them too. Both react fast with water. Handle them with care.

-

Indium (157°C/315°F): Indium is a soft metal. Manufacturers use it to make low-melting alloys and solders. It also works as a clear conductor in screens.

-

Bismuth (271°C/520°F): Bismuth has low toxicity. Drug companies use it in medicines. You’ll find it in cosmetics. It’s also part of safety fuses and some solders.

Low Melting Point Alloys: Eutectic and Specialized Applications

-

Field’s Metal: This eutectic alloy melts at 62°C. Engineers design it for special solders and parts that need exact temperature control.

-

Wood’s Metal: It melts at 70°C. Fire safety systems use it in sprinklers. Model makers use it for detailed casting.

-

Galinstan: This is a gallium-indium-tin alloy. It melts at -19°C. I suggest it for medical thermometers because it contains no mercury. Scientists use it for cooling systems and electrical contacts.

Why Low Melting Point Metals Matter

-

Ease of casting and shaping: You can produce detailed parts without harming other materials. Heat-sensitive components stay safe.

-

Soldering in electronics: These metals let you join electrical parts fast and with precision.

-

Thermal safety devices: These metals and alloys work as fuses, safety plugs, or triggers. They help control heat in many systems.

-

Non-toxic alternatives: I like gallium and Galinstan for this reason. They replace toxic metals like mercury and cadmium.

Selection Considerations

Safety and toxicity: Choose gallium and its alloys if safety matters to you.

Availability and practicality: Francium and cesium melt at lower points. But gallium is easier to get. It’s also safer for everyday use.

Applications: Electronics need these metals for solder and coatings. Safety devices use them as thermofuses. Cooling systems and scientific tools work better with metals that melt well below 300°C.

Quick Reference Melting Points

| Metal/Alloy | Melting Point (°C) | Notable Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Francium | 27 | Research, radioactive |

| Cesium | 28 | Atomic clocks, drilling fluids |

| Gallium | 30 | Electronics, thermometers, alloys |

| Rubidium | 40 | Research |

| Field’s Metal | 62 | Soldering, temperature fixatives |

| Wood’s Metal | 70 | Fire sprinklers, casting molds |

| Galinstan | -19 | Medical thermometers, electronics cooling |

Based on my experience, low melting point metals and alloys are vital for modern tech. They give exact heat control and keep things safe. Gallium-based materials set the standard for both everyday and industrial use.

Metals with the Lowest Melting Points

I find metals with very low melting points fascinating. They’re key for precise heat control and special material needs. Beyond mercury, many pure metals and their alloys melt at much lower temps than standard industrial metals.

Ranking of Low Melting Point Metals (Excluding Mercury)

Francium: Francium melts at just 27°C (81°F). It ranks right below mercury. But here’s the catch: it’s radioactive and super rare. Its half-life is a mere 22 minutes. You can’t use it commercially. Scientists study it in labs, and that’s about it.

Cesium: Cesium melts at 28°C (82°F). Its crystal structure is body-centered cubic. This makes it soft and easy to turn liquid at close to room temperature. I recommend cesium for specialized work. It’s valuable in oil and gas drilling fluids. It also powers atomic clocks with great precision. Based on my experience, its price shows how scarce it is. You’ll pay hundreds of dollars per ounce.

Gallium: Gallium melts at 30°C (86°F). I like this metal because it liquefies just by holding it in your hand. You can also put it in a warm cup and watch it melt. It has an orthorhombic crystal structure. It’s non-toxic, so it’s safer than mercury. Gallium works great in electronics. Semiconductors need it. The non-toxic alloy galinstan uses it too.

Rubidium: Rubidium melts at 40°C (104°F). That’s higher than cesium and gallium. It has a body-centered cubic structure. Researchers use it most. It has some specialized scientific applications.

Potassium and Sodium: Potassium melts at 63°C (145°F). Sodium melts at 98°C (208°F). Both are alkali metals. Fertilizers need them. So do industrial chemicals. They react strongly and feel soft. Their body-centered cubic structures cause this. You need to handle and store them with care.

Indium: Indium melts at 157°C (315°F). It has a body-centered tetragonal structure. It’s soft. It bonds well with other metals. This makes it useful for low-melting alloys. Electronics use it for transparent conductors.

Bismuth, Thallium, and Cadmium: Bismuth melts at 271°C (520°F) with a rhombohedral structure. Thallium melts at 304°C (579°F) with hexagonal close-packed structure. Cadmium melts at 321°C/610°F with hexagonal close-packed structure. All three melt well below common metals like iron or copper. Their unique crystal structures explain why they have lower melting points.

Factors Affecting Melting Points

I suggest looking at several factors. They explain why some metals melt at lower temps:

Bond Strength: Metals with weaker bonds between atoms melt at lower temps.

Crystal Structure: Different structures exist. Body-centered cubic and orthorhombic are examples. These affect how atoms slide past each other.

Atomic Weight and Electron Structure: Heavier atoms can lower the melting point. Certain electron setups do the same.

Practical Applications for Low Melting Point Metals

I find cesium, gallium, and their alloys in high demand. They work well in high-precision fields:

Thermometers and Coolants: Galinstan is a non-toxic alloy. It melts at -19°C. Modern medical thermometers use it. It replaces mercury safely.

Safety Devices and Fuses: Certain alloys use these metals’ low melting points. They work in automatic thermal-release systems. They power safety plugs too.

Specialized Alloys: You’ll find these in soldering. Heat-sensitive fuses need them. Modeling and complex casting use them as well.

Low melting point metals keep driving new ideas in science and industry. I like how they offer safer options than toxic materials. They perform well in temperature-sensitive settings.

Applications of Low Melting Point Metals

I find low melting point metals fascinating. Gallium, indium, Field’s metal, and Cerrolow 117 offer unique benefits in tech, manufacturing, safety, and medical fields. These metals change from solid to liquid at low temperatures. This creates precise solutions that traditional metals can’t match.

Thermal Management and Electronics Cooling

I recommend gallium-based alloys for efficient heat transfer in electronics. CPUs and GPUs use liquid gallium or gallium-indium-tin mixtures (like Galinstan) for cooling. These metals flow over hot surfaces. They keep components cool without causing damage. This works great for AI and data centers. Their low melting point enables direct-contact cooling. You can create advanced thermal interface materials with them.

Precision Soldering and Electronics Work

Eutectic alloys contain bismuth, indium, tin, or lead. They melt at low temperatures. Some melt below 100°C. Electronics workers use them to join circuit components. They’re standard in the industry. These solders protect semiconductors from heat damage. They keep delicate parts safe. This ensures products work reliably.

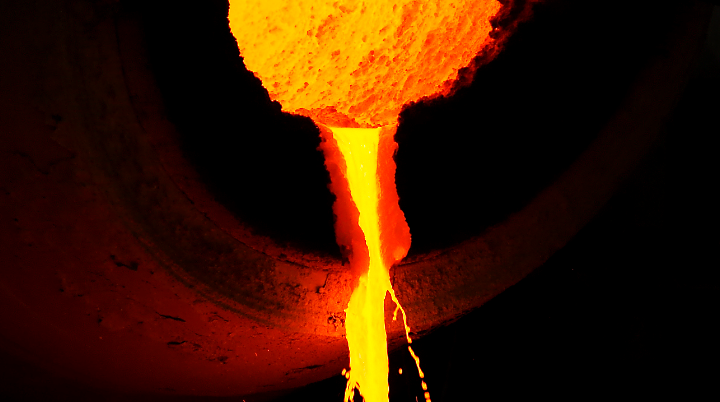

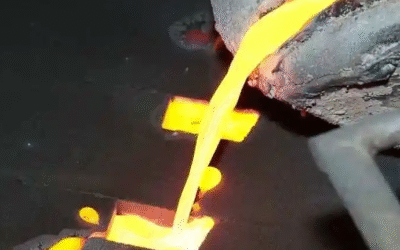

Casting, Molding, and Rapid Prototyping

I suggest Field’s metal (62°C) and Cerrolow 117 (47°C) for small batch die casting. They’re practical and economical. They’re perfect for rapid prototyping. You can pour these alloys into 3D-printed plastic molds. The molds won’t melt. You can develop and adjust prototypes quickly. This works for research or short production runs. The setup costs stay low.

Medical and Dental Applications

Bismuth-based alloys work well for medical and dental impressions. They melt and pour without difficulty. Then they solidify to create detailed molds. These molds capture dental or body shapes for prosthetics and restorative work.

Temporary Work-Holding and Industrial Finishing

Fusible alloys secure fragile workpieces. I’ve seen them used for lens blocking and turbine blade finishing. You melt the alloy around the part. It holds tight during processing. Then you reheat it and remove it. No damage occurs. No residue remains.

Thermal Safety Devices and Fire Protection

Thermal fuses and fire sprinkler triggers use alloys like Wood’s metal (70°C). These alloys melt at set temperatures. Fire or overheating causes the alloy to melt. This activates safety mechanisms. No electronics are needed. The physical response is reliable.

Tube and Pipe Bending

Plumbing and HVAC industries use alloys in the 70–150°C range. They fill pipes during bending. The process is straightforward: Pour in the molten alloy. Bend the tube without kinking. Melt the alloy out. You get smooth, undamaged bends.

3D Printing & Metallization

Room-temperature liquid metals like gallium and indium alloys print direct 3D metallic structures. These prints conduct electricity well. They contain up to 97.5% metal. Based on my experience, they’re changing soft robotics, wearable electronics, and flexible circuits.

Summary Table of Common Low Melting Alloys & Elements

| Alloy/Element | Melting Point (°C) | Sample Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Field’s Metal | 62 | Casting, soldering, thermal regulation |

| Cerrolow 117 | 47 | Precision casting, safety devices |

| Wood’s Metal | 70 | Fire sprinklers, molds |

| Rose’s Metal | 94 | Soldering, fuses |

| Gallium | 29.8 | Electronics cooling, 3D printing |

| Indium | 156.6 | Solders, electronics, conductors |

| Bismuth | 271.4 | Medical alloys, fire safety, cosmetics |

I believe low melting point metals are essential in modern manufacturing. They’re vital for electronics cooling, safety, and health fields. They melt at specific temperatures. This allows for customized, efficient, and safe uses across industries.

Importance of Melting Points in Metalworking

I recommend understanding melting points of metals in metalworking. It impacts how metals can be processed, shaped, and used in industry and technology. Every metal has its own unique melting point. This determines the exact temperature needed for smelting, casting, or welding.

Why Melting Points Matter in Metalworking

Choosing the Right Processing Method: Metals with lower melting points, like gallium (30°C), can be melted with simple heating. Sometimes you can even melt it in your palm. Metals such as tin (232°C) and lead (327°C) need higher heat sources. But these temperatures are still manageable for practical metalworking.

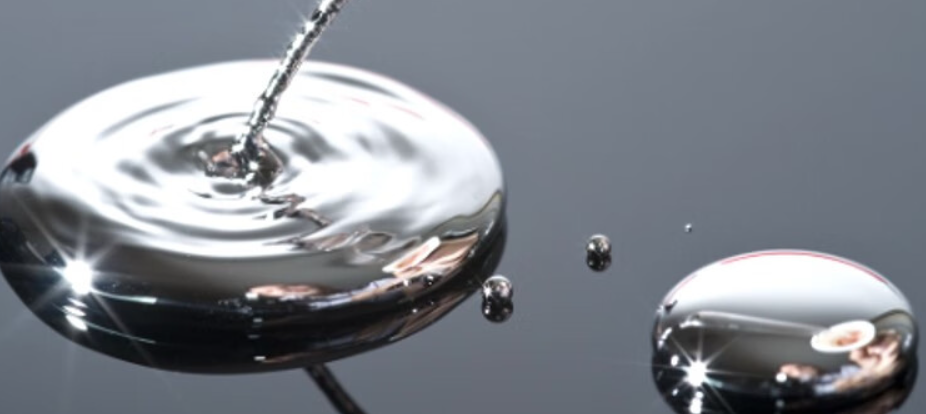

Picking the Correct Equipment: The melting point influences the choice of furnaces, molds, and tools. For instance, to smelt or cast lead, equipment must handle temperatures above 327°C. This prevents failure and ensures a smooth process.

Avoiding Material Failure: Using a metal in environments near or above its melting point can cause breakdowns. For example, a safety plug made from gallium melts in overheating events. It acts as a fuse. A jet engine nozzle must stay well below its material’s melting point to avoid accidents.

Matching Metals to Applications: I suggest using low melting point metals for jobs where quick melting is needed. These include safety fuses, emergency plugs, or low-temperature soldering in sensitive electronics.

Safety and Process Efficiency: Lower melting temperatures allow safer working conditions. They help manufacturers use less energy. This saves both money and effort compared to metals that require extreme heat.

Key Metals and Alloys by Melting Point (Excluding Mercury)

- Gallium: 30°C (86°F) — used in safety plugs and thermometers

- Francium: 27°C (81°F) — rare and radioactive, not practical for industry

- Cesium: 28°C (82°F) — valuable but scarce, used in precision fluid drilling

- Rubidium: 40°C (104°F) — scientific use

- Potassium: 63°C (145°F) — needs careful handling, used in chemicals and fertilizers

- Sodium: 98°C (208°F) — reactive, used in industry

- Indium: 157°C (315°F) — key for low-temperature solders

- Tin: 232°C (450°F) — mainstay in soldering and casting

- Lead: 327°C (621°F) — batteries, solder, and casting applications

Practical Metalworking Applications

Casting Alloys: Low-melting alloys like tin-lead make plumbing joints and electronic solders easy to produce. They are reliable.

Soldering in Electronics: Indium-based or tin-based solders melt at lower temperatures. This protects sensitive electronic components during assembly. I prefer these for delicate work.

Fusible Safety Devices: Gallium and specialized alloys are made for fire safety fuses. They melt on overheating and activate protective mechanisms. Based on my experience, these are critical safety components.

Quick Reference: Melting Points and Industrial Uses

| Metal | Melting Point (°C) | Common Use Example |

|---|---|---|

| Gallium | 30 | Thermometers, safety plugs, fusible alloys |

| Indium | 157 | Low-temperature solder, electronic sealing |

| Tin | 232 | Soldering, tinplate, casting alloys |

| Lead | 327 | Weighted products, solder alloys, batteries |

Why Accurate Melting Point Knowledge Matters

Manufacturers, engineers, and designers depend on accurate melting point data. They use it to select the right metal for each application. This ensures production safety. It ensures optimal product strength. It ensures efficient use of energy and resources. I believe this knowledge drives reliable, safe, and cost-effective outcomes in every area of metalworking. Knowing these points helps you make better decisions in your projects.

Comparison of Melting Points Across Metals

I find that knowing metal melting points helps explain why we pick certain materials for specific jobs. Some metals melt fast. Others can take intense heat.

Key Low Melting Point Metals (Excluding Mercury)

Gallium — Melts at 29.76°C (85.57°F). It turns liquid in your hand. I’ve seen it used in thermometers, semiconductors, and liquid mirrors.

Cesium — Melts at 28.5°C (83.3°F). This metal is rare and costs hundreds of dollars per ounce. People use it for atomic clocks and drilling fluids.

Rubidium — Melts at 39.3°C (102.8°F). Scientists use it for research projects.

Indium — Melts at 156.6°C (313.9°F). You need this for solders and touchscreens.

Tin — Melts at 231.9°C (449.4°F). Many people use it for soldering.

Lead — Melts at 327.5°C (621.5°F). We know it from batteries and old plumbing.

High Melting Point Metals: Industrial Strength

Tungsten — This metal has the highest natural melting point at 3422°C (6191°F). I recommend it for light bulb filaments, aerospace parts, and industrial heating elements.

Rhenium and Molybdenum — These come next. Engineers use them for jet engines and high-performance gear.

Melting Point Ranges and Use Cases

- Very Low (<100°C): Mercury, gallium, cesium, rubidium. These work great for precision thermometers, fluid cooling, and special electronics.

- Moderate (100–500°C): Indium, tin, lead, bismuth, zinc. Workers use these in solders, casting alloys, batteries, and plating.

- High (500–1500°C): Aluminum, copper, iron, nickel. These are common structural and industrial metals. They need high-temperature processing.

- Ultra High (>2500°C): Tungsten, rhenium, osmium, tantalum. Factories need these for heat shields, aerospace, and furnace parts.

Melting Point Table

| Metal | Melting Point (°C) | Melting Point (°F) |

|---|---|---|

| Mercury | -38.86 | -37.95 |

| Gallium | 29.76 | 85.57 |

| Cesium | 28.5 | 83.3 |

| Rubidium | 39.3 | 102.8 |

| Indium | 156.6 | 313.9 |

| Tin | 231.9 | 449.4 |

| Lead | 327.5 | 621.5 |

| Zinc | 419.5 | 787.1 |

| Aluminum | 660.3 | 1220.5 |

| Copper | 1084.6 | 1984.3 |

| Iron | 1538 | 2800 |

| Nickel | 1455 | 2651 |

| Tungsten | 3422 | 6191 |

| Rhenium | 3186 | 5767 |

| Osmium | 3025 | 5477 |

Application Highlights by Melting Point

Low melting metals work well in thermal response systems. I suggest them for electronics, safety fuses, and cooling systems.

High melting metals give you strong structures. They resist harsh conditions. This makes them great for aerospace and power generation.

Summary: Why Melting Point Matters

Metals have huge differences in melting points. Mercury is liquid at room temperature. Tungsten resists extreme heat. These differences decide how we use them in industry, science, electronics, and safety. I believe picking the right metal starts with knowing how it handles heat.